audio/visual version

This book review has spurred me to offer a brief follow up to a previous post on free will.

I agree with the review author Holly Anderson, who dismisses the idea that "emergence," or the consideration that brain functioning as a whole is more than the sum of its parts, by pointing out that any process governed by the brain is deterministic. However, focus of this post is on the issue of whether this means people shouldn't be held responsible for their actions.

The answer, in my opinion, is that in a pure abstract moral sense they can't be, but we have to assign responsibility to those who engage in externally damaging behavior anyway, for practical reasons. We have to protect society.

By the way, it is interesting to me that the question of whether a lack free will cancels moral responsibility is only considered with respect to negative behavior, at least in my experience.

Quantitative Psychological Theory and Musings

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Free Will Absolution?

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

behaviorm,

determinism,

emergence,

free will,

My Brain Made Me Do It,

negative externalities,

neuroscience

Friday, March 26, 2010

Suicide is Adaptive(Evolutionarily)

audio/visual version

Update: This post is not meant to advocate suicide. It only speaks to evoluationary motives.

Suicide is often a natural behavior. This is because it may help to pass genes.

This seeming paradox is resolved when you consider the implications of inclusive fitness, or more specifically with regard to kinship selection. This refers to the fact that close relatives have a high number of genes in common, the hence the passing on of shared genes sometimes benefits from sacrifices at the expense of one or more relatives, even leading to death. Particularly, individuals with low access to resources needed to pass genes directly, relative to family members, become a drag on the resources of others in the family.

This idea was perhaps first put forth by Denys deCatanzaro, but the logic first appealed to me years before I found this paper and related research.

This is not to say that all cases of suicide are related to kinship selection, but does suggest the existence of a sort of "mental program" that is activated by low moods, relative to family members. Other causes for suicide include the metacognitive avoidance of psychical and or physical pain, the influence of psychoactive drugs, and more purely neurological causes.

Update: This post is not meant to advocate suicide. It only speaks to evoluationary motives.

Suicide is often a natural behavior. This is because it may help to pass genes.

This seeming paradox is resolved when you consider the implications of inclusive fitness, or more specifically with regard to kinship selection. This refers to the fact that close relatives have a high number of genes in common, the hence the passing on of shared genes sometimes benefits from sacrifices at the expense of one or more relatives, even leading to death. Particularly, individuals with low access to resources needed to pass genes directly, relative to family members, become a drag on the resources of others in the family.

This idea was perhaps first put forth by Denys deCatanzaro, but the logic first appealed to me years before I found this paper and related research.

This is not to say that all cases of suicide are related to kinship selection, but does suggest the existence of a sort of "mental program" that is activated by low moods, relative to family members. Other causes for suicide include the metacognitive avoidance of psychical and or physical pain, the influence of psychoactive drugs, and more purely neurological causes.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

adaptive behavior,

adaptive suicide,

Denys deCatanzaro,

inclusive fitness,

kinship,

kinship selection,

suicide

Sunday, March 21, 2010

6 Days and No Longer Counting

I apologize for my lack of posts over the last six days. Everyday, I've been busier than anticipated, always thinking that finishing one or more posts I've been working on was coming the very next day or night. Hence, I didn't post a message revealing any intention to take a break from posting.

Unfortunately, my posts sometimes take hours to complete, given the research requirements. Sometimes searching for and/or actually obtaining relevant papers create unanticipated delays, apart from unexpected changes in my general schedule.

I will try to post more frequently whatever my schedule, but let you know when I'm not certain about the length of a delay. Thank you for sticking with me.

Unfortunately, my posts sometimes take hours to complete, given the research requirements. Sometimes searching for and/or actually obtaining relevant papers create unanticipated delays, apart from unexpected changes in my general schedule.

I will try to post more frequently whatever my schedule, but let you know when I'm not certain about the length of a delay. Thank you for sticking with me.

Depressed Parents Play Favorites

audio/visual version

The model of behavioral investment as determined by mood that I previously presented has an interesting implication for the way parents treat their children. That is, depressed parents are more likely to succumb to favoritism. Specifically, as mood decreases, parental investment shifts toward children deemed more reproductively fit(1).

Parental investment involves the amount of time, energy, and other resources offered each child by their parents(2), and reproductive fitness(3) can be revealed in signals related to physical attractiveness(cuteness, etc), physical fitness, intelligence, emotional robustness, susceptibility to illness, ability to make friends, and even resemblance to one or both parents, among other cues. There is even evidence that birth weight is moderated by a mother's stress levels(lower mood), with higher stress associated with lower weights.

This is part of a larger phenomenon(first link above) in which depressed parents often unconsciously develop high quantity, low parental investment reproductive strategies in environments peceived as hostile to higher per-child investment strategies.

1. D. Beaulieu, D. Bugental (July 2008) Contingent parental investment: an evolutionary framework for understanding early interaction between mothers and children.

Evolution and Human Behavior, Volume 29, Issue 4, Pages 249-255

2. Trivers, R.L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871-1971 (pp. 136-179). Chicago, IL: Aldine.

3. Hamilton, W.D. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behavior. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7:1-52

The model of behavioral investment as determined by mood that I previously presented has an interesting implication for the way parents treat their children. That is, depressed parents are more likely to succumb to favoritism. Specifically, as mood decreases, parental investment shifts toward children deemed more reproductively fit(1).

Parental investment involves the amount of time, energy, and other resources offered each child by their parents(2), and reproductive fitness(3) can be revealed in signals related to physical attractiveness(cuteness, etc), physical fitness, intelligence, emotional robustness, susceptibility to illness, ability to make friends, and even resemblance to one or both parents, among other cues. There is even evidence that birth weight is moderated by a mother's stress levels(lower mood), with higher stress associated with lower weights.

This is part of a larger phenomenon(first link above) in which depressed parents often unconsciously develop high quantity, low parental investment reproductive strategies in environments peceived as hostile to higher per-child investment strategies.

1. D. Beaulieu, D. Bugental (July 2008) Contingent parental investment: an evolutionary framework for understanding early interaction between mothers and children.

Evolution and Human Behavior, Volume 29, Issue 4, Pages 249-255

2. Trivers, R.L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871-1971 (pp. 136-179). Chicago, IL: Aldine.

3. Hamilton, W.D. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behavior. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7:1-52

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

depression,

favoritism,

inclusive fitness,

parental investment,

reproductive fitness

Monday, March 15, 2010

No Allergies or Immunity to Learning

audio/visual version

This post can be considered an extension of my last one on learned tolerance to addictive substances.

Like reactions to addictive substances, allergic and immune responses are influenced by external environments and mental states. Both can be learned and forgotten, depending on the contexts. I lump them together here, because they are actually both functions of the immune system.

Both types of responses can be triggered by external environments and mental states that are similar to those in which allergens(former) or pathogens(for example, latter) were previously encountered. Likewise, learned responses can fail to occur in environments and or mental states that are subjectively dissimilar. So, when it comes to the acquisition and extinction(unlearning) of allergies and specific immune responses, all of the principles of learning apply.

One implication is that exposure treatments, involving the gradual presentation of contexts(stimuli) previously experienced with an allergen or pathogen, sans those threats, should sometimes diminish learned allergic and immune responses. This is similar to systematic desensitization treatments used to treat phobias and more general anxiety disorders. Perhaps this approach can also apply to treatment for some cases of autoimmune disorders.

So, this is just another example of how psychology can touch upon elements of the functioning of our bodies in what may be unexpected ways for many.

This post can be considered an extension of my last one on learned tolerance to addictive substances.

Like reactions to addictive substances, allergic and immune responses are influenced by external environments and mental states. Both can be learned and forgotten, depending on the contexts. I lump them together here, because they are actually both functions of the immune system.

Both types of responses can be triggered by external environments and mental states that are similar to those in which allergens(former) or pathogens(for example, latter) were previously encountered. Likewise, learned responses can fail to occur in environments and or mental states that are subjectively dissimilar. So, when it comes to the acquisition and extinction(unlearning) of allergies and specific immune responses, all of the principles of learning apply.

One implication is that exposure treatments, involving the gradual presentation of contexts(stimuli) previously experienced with an allergen or pathogen, sans those threats, should sometimes diminish learned allergic and immune responses. This is similar to systematic desensitization treatments used to treat phobias and more general anxiety disorders. Perhaps this approach can also apply to treatment for some cases of autoimmune disorders.

So, this is just another example of how psychology can touch upon elements of the functioning of our bodies in what may be unexpected ways for many.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

acquired allergies,

acquired immune responses,

allergies,

autoimmune,

exposure therapy,

immune responses,

immune system,

systematic desensitization

Friday, March 12, 2010

Drug Tolerance in Context(Really)

audio/visual version

Drug tolerance is contextual. It can vary, depending on the external environment and even the thoughts of the user. The key idea is that tolerance-related drug potency increases in unfamilar environments or mental states.

There is much research that bears this out, with experiments going back to at least 1975. Overdoses are even thought to have occurred as a result. This suggests that tolerance often has a strong element of learning, despite what many students in my substance abuse classes inititally think. You should see their faces.

This obviously has implications for addiction, as the higher the tolerance to an addictive drug, the lower the pleasure of using, but the more severe the negative consequences for abstaining. And of course, many seemingly hold the idea that familiar environments in which drug use occurs tempt addicted users. Hence, the encouragement given to many substance abuse patients is to avoid such environments, along with changing some of the ways they think about their addictions and any related problems. Perhaps the danger of patients using in novel contexts with increased enjoyment is often overlooked as a risk for relapse.

Any "highs" addicted users enjoy are not the only experiential aspects that suffer tolerance. There are many other physiological effects that are also context-dependent. For example, take the antinociceptive(pain relief) effects of opiates.

Interestingly, there is a flip side of learned tolerance. This involves the use of cues for drug consumption to elicit feelings of intoxication. There are many experiments in which participants are given alcohol placebos and report and otherwise display evidence of intoxication. There is also a humorous video here.

Finally, I offer a hypothesis. Since learned drug tolerance fails to transfer to the degree that a context is novel, it should hence diminish during laughter. Given that laughter involves gain/loss-independent expectancy violations, this would seem a safe bet(1). I'm still looking for a study to address this question. If any of you find one, please let me know.

1. Nerhardt, G. Humor and inclinations of humor: Emotional reactions to stimuli of different divergence from a range of expectancy. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1970, 11, 185-195.

Drug tolerance is contextual. It can vary, depending on the external environment and even the thoughts of the user. The key idea is that tolerance-related drug potency increases in unfamilar environments or mental states.

There is much research that bears this out, with experiments going back to at least 1975. Overdoses are even thought to have occurred as a result. This suggests that tolerance often has a strong element of learning, despite what many students in my substance abuse classes inititally think. You should see their faces.

This obviously has implications for addiction, as the higher the tolerance to an addictive drug, the lower the pleasure of using, but the more severe the negative consequences for abstaining. And of course, many seemingly hold the idea that familiar environments in which drug use occurs tempt addicted users. Hence, the encouragement given to many substance abuse patients is to avoid such environments, along with changing some of the ways they think about their addictions and any related problems. Perhaps the danger of patients using in novel contexts with increased enjoyment is often overlooked as a risk for relapse.

Any "highs" addicted users enjoy are not the only experiential aspects that suffer tolerance. There are many other physiological effects that are also context-dependent. For example, take the antinociceptive(pain relief) effects of opiates.

Interestingly, there is a flip side of learned tolerance. This involves the use of cues for drug consumption to elicit feelings of intoxication. There are many experiments in which participants are given alcohol placebos and report and otherwise display evidence of intoxication. There is also a humorous video here.

Finally, I offer a hypothesis. Since learned drug tolerance fails to transfer to the degree that a context is novel, it should hence diminish during laughter. Given that laughter involves gain/loss-independent expectancy violations, this would seem a safe bet(1). I'm still looking for a study to address this question. If any of you find one, please let me know.

1. Nerhardt, G. Humor and inclinations of humor: Emotional reactions to stimuli of different divergence from a range of expectancy. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1970, 11, 185-195.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

addiction,

classical conditioning,

drug abuse,

drug tolerance,

learned tolerance,

placebo intoxication,

tolerance

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Does Depression Cause Neurons to Commit Suicide?

audio/visual version

Sandeep Gautam has a nice post on his blog about the effects of depression on hippocampal cells.

The story is that chronically high levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, kills these neurons. Depression leads to elevated average cortisol levels, as lower moods make negative emotional responses, such as anger and anxiety, more severe. Worse, the hippocampus is also responsible for down-regulating stress levels, the shrinking mass thereof creating an inertia with respect to increases in mood, both short and long term. So, climbing out of depression is harder, the more severe the depression and the longer its duration. Fortunately, hippocampal cells are born anew with increased average mood levels over a sufficient period of time, increasing the brain's ability to downregulate stress.

I interpret this as representing the physiological mechanism by which low average mood levels demand higher net levels of reinforcement over the longer term to reduce depression-related risk aversion, in the risk averse. This serves the behavioral economic purpose of requiring more evidence that an environment long seen as hostile to the goal of secure reproduction has become more hospitable. This is the equivalent of not trusting someone who is long seen as a jerk, but acts somewhat nicer on a given day. The trust in the change doesn't come overnight, and nor should a trust in what is normally an inhospitable enviornment.

Sandeep Gautam has a nice post on his blog about the effects of depression on hippocampal cells.

The story is that chronically high levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, kills these neurons. Depression leads to elevated average cortisol levels, as lower moods make negative emotional responses, such as anger and anxiety, more severe. Worse, the hippocampus is also responsible for down-regulating stress levels, the shrinking mass thereof creating an inertia with respect to increases in mood, both short and long term. So, climbing out of depression is harder, the more severe the depression and the longer its duration. Fortunately, hippocampal cells are born anew with increased average mood levels over a sufficient period of time, increasing the brain's ability to downregulate stress.

I interpret this as representing the physiological mechanism by which low average mood levels demand higher net levels of reinforcement over the longer term to reduce depression-related risk aversion, in the risk averse. This serves the behavioral economic purpose of requiring more evidence that an environment long seen as hostile to the goal of secure reproduction has become more hospitable. This is the equivalent of not trusting someone who is long seen as a jerk, but acts somewhat nicer on a given day. The trust in the change doesn't come overnight, and nor should a trust in what is normally an inhospitable enviornment.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

anxiety,

behavioral economics,

cortisol,

depression,

fear,

hippocampal,

hippocampus,

mood,

stress

Monday, March 8, 2010

Coming Soon: Auditory Posts

audio/visual version

I am in the process of converting my blog posts into audio and am proceeding as quickly as time allows. There will be a link at the top of most posts allowing you to listen instead of read, or do both. Feel free to let me know what you think!

I am in the process of converting my blog posts into audio and am proceeding as quickly as time allows. There will be a link at the top of most posts allowing you to listen instead of read, or do both. Feel free to let me know what you think!

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

audio blog posts,

video blog post,

vlog,

vlogging

Saturday, March 6, 2010

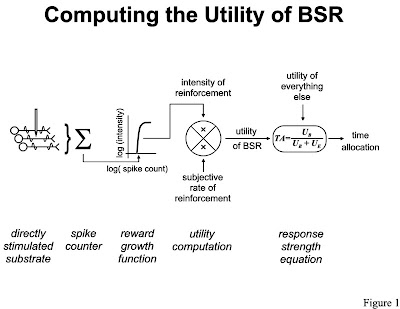

Neural Utility Paper with a Great Chart

I just found a great chart in a fascinating Shizgal paper on the neural basis for utility. The paper is available for free.

The chart takes one from neural stimulation to behavior(click to enlarge):

The chart takes one from neural stimulation to behavior(click to enlarge):

Notice the matching law equation I refer to and reinterpret in my first post on this blog.

Friday, March 5, 2010

No Free Lunch, or Will for that Matter

Audio/Visual Version

I was in a conversation the other night and was asked whether I believe in free will. I don't, and haven't for sometime. I have many reasons, including the fact that I see no reason why we can't explain all of human action and cognitiion without it. But last night, I thought of a new reason that should be obvious.

As long as we have needs and resources are scarce, there can't be anything like free will, at least in the either/or sense. We will always ultimately be controlled by such needs, toward the goal of passing on our genes. But, what of people who claim free will exists in a limited sense, like my interlocutor?

I've never bought this concept. At best, they can say that we sometimes have free will to a degree. But, assuming that "free will" refers to a conscious decision process, the processes by which conscious and unconscious decisions are made are mostly the same. The same needs exist, along with the same laws of learning. The latter just in a metacognitive sense with respect to consciousness.

I was in a conversation the other night and was asked whether I believe in free will. I don't, and haven't for sometime. I have many reasons, including the fact that I see no reason why we can't explain all of human action and cognitiion without it. But last night, I thought of a new reason that should be obvious.

As long as we have needs and resources are scarce, there can't be anything like free will, at least in the either/or sense. We will always ultimately be controlled by such needs, toward the goal of passing on our genes. But, what of people who claim free will exists in a limited sense, like my interlocutor?

I've never bought this concept. At best, they can say that we sometimes have free will to a degree. But, assuming that "free will" refers to a conscious decision process, the processes by which conscious and unconscious decisions are made are mostly the same. The same needs exist, along with the same laws of learning. The latter just in a metacognitive sense with respect to consciousness.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

determinism,

determinist,

free will,

learning,

responsibility,

scarcity

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Another Busted Myth: 5 Senses

I may as well post this now, for those who like shorter, punchier offerings. It is commonly taught and repeated that we have 5 senses. Well, we don't. We have at least 7. Below is a section from my very last post, which was on the subject of learning:

...senses include sight, hearing, touch, smell, pain, proprioception, and some vestibular system functions. The latter two are not commonly thought of as senses, but demonstrably are. Proprioception is revealed as the ability to know the orientation of your limbs, even though you are not using sight, hearing, touch, or pain reception to supply such information. The vestibular system allows you to know the orientation of your entire body, without the use of the above mentioned first five senses, when the system is relatively unperturbed. Hence it offers critical input facilitating walking or other activities that require balance.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

5 senses,

proprioception,

senses,

vestibular

Learning: A Section from My Anger Management Handout

I am too busy and lazy right now to offer a simple post on anger, so below is a barely altered section from an anger management handout I offer students. I start from the perspective of learned expectations.

Expectations:

Expectations are learned or unlearned predictions about the occurrence or non-occurrence of at least two stimuli, or events. Stimuli, or a stimulus in the singular, is anything that is detectable by your senses, or any representation of thereof within your brain. These senses include sight, hearing, touch, smell, pain, proprioception, and some vestibular functions. The latter two are not commonly thought of as senses, but demonstrably are. Proprioception is revealed as the ability to know the orientation of your limbs, even though you are not using sight, hearing, touch, or pain reception to supply such information. The vestibular system allows you to know the orientation of your entire body, without the use of the above mentioned first five senses, when the system is relatively unperturbed. Hence it offers critical input facilitating walking or other activities that require balance. Detection of stimuli can occur with or without your conscious awareness, but what is conscious awareness and is there an unconscious awareness?

Of Two Minds

The brain has many separate memory systems, but we will only focus on the two broadest categories. The first is explicit memory, which is memory that you can consciously, if not always consistently, recall. The second is implicit memory, and it changes and can be recalled without need of conscious awareness, though you may have some awareness it is occurring. The senses feed these two memory systems in order from the implicit to the explicit.

The implicit has more direct and immediate attachment to emotional centers in the brain, such as the amygdala, and hence has the first opportunity to affect the emotions that drive your behavior. This is why you sometimes react emotionally without having time to “think” first.

The explicit system takes a longer course, with the detour to the implicit, eventually sending signals to the prefrontal cortex, which facilitates conscious memory and thought. Then, some conscious thought may be stimulated, as non-activation of the amygdala (emotions) allows and then the circuit is completed when signals travel back to the amygdala. This is how your thoughts can influence your emotional responses. As mentioned above, the implicit system dominates at the expense of the explicit as emotions become stronger. Perhaps you’ve noticed that it is harder to consciously recall certain information that is otherwise easily retrievable when you are upset. You may also notice how much harder it is to think. This is one of the reasons it is critical to avoid anger responses in the first place, as will be covered in more detail later

The implicit memory system is “recording” or learning associations between stimuli or events, even as your conscious mind may be focused on other things. It records through the senses, so you can only learn what your senses are in a position to detect. With this in mind, learning can take place on two levels simultaneously, though, the implicit dominates. This is how phobias are learned, for example, and can be triggered sometimes by stimuli you may not consciously notice, but which trigger extreme emotional responses and behavior you cannot necessarily consciously control. The same is true of traumatic memories, or the learning of any kind of information. Hence, to understand what expectations are and how they develop, one must understand the basic principles of learning. The basic physiology has just been covered for our purposes, so we now move to what is going on in the external world, as detected by your brain.

Learn the Basics

Some of the basic principles of learning include processes of generalization, discrimination, and transitivity, all with respect to two or more stimuli.

Generalization involves carrying learned stimuli associations of one context, referred to as a predictive context, to another. Associations, in the simplest form, merely involve the detected tendency of at least two stimuli to occur together or be seen as similar in some way. For example, someone new to the planet may notice a motor vehicle for the first time and see that it has four wheels. Upon seeing another on different street, the alien begins to generalize the expectation that motor vehicles will have four wheels. The expectation grows, the more four-wheeled vehicles the alien sees in different situations. Hence, generalization can occur either by noticing the same relationship among stimuli in a new overall, distinguishable context, or by simply “automatically” seeing two situations as similar, without the need to sense it directly in the first place. This latter ability to generalize is known as transitivity, which will be covered in a moment.

First, however, discrimination simply involves the ability to distinguish two stimuli or two situations or contexts from each other. It is the ability to detect and notice differences that may or may not be relevant for the outcome of importance to the observer. An example of discrimination might involve our alien first witnessing many cars with four wheels, but then encountering a motorcycle with 2 wheels, and hence, since cars and motorcycles are easily distinguishable in a number of ways, making the discrimination between motorcycles and cars, expecting four wheels on cars and two on motorcycles. The more motorcycles the alien sees, the more generalized the discrimination becomes, and hence the greater the expectation that motorcycles will have two wheels. So, discriminations depend on generalization, either directly or indirectly, for this form of learning to occur.

Generalization takes place indirectly through transitivity. This is the innate ability to immediately recognize that, for example, if a = b and b = c, then a = c. This can occur automatically, without the need for any direct training as it is commonly conceived, and is naturally facilitated by the structure of the brain and the automatic way elements of stimuli that are similar are associated. It is this process that allows for generalization or the generalization of discriminations to occur through the process of imagination and is in fact the very stuff of imagination. So, for example, the alien can now imagine a motor vehicle with three wheels, or any number of wheels, without first seeing one. The alien can expect that a three-wheeled vehicle may exist or would be possible to build.

These three different processes of learning are complementary and can feed each other in constant loops. This fact, along with those of first focus above, goes a long way in describing what thinking and learning are. However, there is another property of learning worth noting, before turning to motivation to complete our description of anger responses.

This property is called blocking. This is when a previously learned association, either learned directly in the sensory environment or indirectly through transitivity, literally “blocks” the learning of other associations. Blocking occurs due to the practical limitations of our brain and sensory systems. We can only detect and process so much information at one time, and so we will only expend our limited resources in proportion to what we deem important. In other words, the environment often presents us with more information than we can process at any one time and we implicitly and or explicitly make choices about what to use our limited sensory and thought capacity to focus on. Hence, there is information in the environment that we may process late, relative to our welfare, or perhaps not at all. To illustrate, during his first minutes on earth, our alien may have noticed that there are at least two types of motor vehicles, one with four wheels and another with two. So, spending some time making and thinking about these observations, the alien suddenly notices that his delicate, relatively light-deprived skin is getting red. The alien has now learned a new lesson, though all too late, as his sensory focus and attention was on the cars and motorcycles going by. That is, that the earth’s sunlight is too intense for his delicate skin and he must now seek shelter or cover.

In extreme cases, blocking can not only delay learning, but prevent it entirely, permanently. For instance, if one develops a learned habit of focusing on only certain elements of a situation or even abstract concepts, one can easily miss differences either present from the beginning or that arise later. This can even occur with imagination, though imagination also offers another way to check against blocking. Can you imagine how this can occur?

To mention another example, in the experimental case, rats that are trained to press a lever to receive a food pellet after seeing a red light will later fail to learn to press in response to a yellow light of similar brightness, if the yellow light is first presented after learning to focus on the red light occurs. In this case, the yellow light is then presented alone and the rat will not press the lever for food.

It is important to refer to two previous concepts here, which are those of implicit and explicit memory. The newer and/or more complex the learning that is occurring, the more sensory and conscious (explicit) processing that is required. As associations are better learned, the behaviors they help motivate depend increasingly on implicit memory as learned behaviors become increasingly automatic, eventually occurring with little or no thought. This is what we call “habit” formation, and it occurs at a rate and in proportion to the sensory intensity, subjective importance, and distinguishability of the relevant stimuli.

That's the end of the section from my handout. There is more to mention here though regarding the complexity of the environments in which brains learn. One of the implications is an explanation for why people often seem to repeat mistakes, even many, many times.

Below is a section of a recent blog post:

Expectations:

Expectations are learned or unlearned predictions about the occurrence or non-occurrence of at least two stimuli, or events. Stimuli, or a stimulus in the singular, is anything that is detectable by your senses, or any representation of thereof within your brain. These senses include sight, hearing, touch, smell, pain, proprioception, and some vestibular functions. The latter two are not commonly thought of as senses, but demonstrably are. Proprioception is revealed as the ability to know the orientation of your limbs, even though you are not using sight, hearing, touch, or pain reception to supply such information. The vestibular system allows you to know the orientation of your entire body, without the use of the above mentioned first five senses, when the system is relatively unperturbed. Hence it offers critical input facilitating walking or other activities that require balance. Detection of stimuli can occur with or without your conscious awareness, but what is conscious awareness and is there an unconscious awareness?

Of Two Minds

The brain has many separate memory systems, but we will only focus on the two broadest categories. The first is explicit memory, which is memory that you can consciously, if not always consistently, recall. The second is implicit memory, and it changes and can be recalled without need of conscious awareness, though you may have some awareness it is occurring. The senses feed these two memory systems in order from the implicit to the explicit.

The implicit has more direct and immediate attachment to emotional centers in the brain, such as the amygdala, and hence has the first opportunity to affect the emotions that drive your behavior. This is why you sometimes react emotionally without having time to “think” first.

The explicit system takes a longer course, with the detour to the implicit, eventually sending signals to the prefrontal cortex, which facilitates conscious memory and thought. Then, some conscious thought may be stimulated, as non-activation of the amygdala (emotions) allows and then the circuit is completed when signals travel back to the amygdala. This is how your thoughts can influence your emotional responses. As mentioned above, the implicit system dominates at the expense of the explicit as emotions become stronger. Perhaps you’ve noticed that it is harder to consciously recall certain information that is otherwise easily retrievable when you are upset. You may also notice how much harder it is to think. This is one of the reasons it is critical to avoid anger responses in the first place, as will be covered in more detail later

The implicit memory system is “recording” or learning associations between stimuli or events, even as your conscious mind may be focused on other things. It records through the senses, so you can only learn what your senses are in a position to detect. With this in mind, learning can take place on two levels simultaneously, though, the implicit dominates. This is how phobias are learned, for example, and can be triggered sometimes by stimuli you may not consciously notice, but which trigger extreme emotional responses and behavior you cannot necessarily consciously control. The same is true of traumatic memories, or the learning of any kind of information. Hence, to understand what expectations are and how they develop, one must understand the basic principles of learning. The basic physiology has just been covered for our purposes, so we now move to what is going on in the external world, as detected by your brain.

Learn the Basics

Some of the basic principles of learning include processes of generalization, discrimination, and transitivity, all with respect to two or more stimuli.

Generalization involves carrying learned stimuli associations of one context, referred to as a predictive context, to another. Associations, in the simplest form, merely involve the detected tendency of at least two stimuli to occur together or be seen as similar in some way. For example, someone new to the planet may notice a motor vehicle for the first time and see that it has four wheels. Upon seeing another on different street, the alien begins to generalize the expectation that motor vehicles will have four wheels. The expectation grows, the more four-wheeled vehicles the alien sees in different situations. Hence, generalization can occur either by noticing the same relationship among stimuli in a new overall, distinguishable context, or by simply “automatically” seeing two situations as similar, without the need to sense it directly in the first place. This latter ability to generalize is known as transitivity, which will be covered in a moment.

First, however, discrimination simply involves the ability to distinguish two stimuli or two situations or contexts from each other. It is the ability to detect and notice differences that may or may not be relevant for the outcome of importance to the observer. An example of discrimination might involve our alien first witnessing many cars with four wheels, but then encountering a motorcycle with 2 wheels, and hence, since cars and motorcycles are easily distinguishable in a number of ways, making the discrimination between motorcycles and cars, expecting four wheels on cars and two on motorcycles. The more motorcycles the alien sees, the more generalized the discrimination becomes, and hence the greater the expectation that motorcycles will have two wheels. So, discriminations depend on generalization, either directly or indirectly, for this form of learning to occur.

Generalization takes place indirectly through transitivity. This is the innate ability to immediately recognize that, for example, if a = b and b = c, then a = c. This can occur automatically, without the need for any direct training as it is commonly conceived, and is naturally facilitated by the structure of the brain and the automatic way elements of stimuli that are similar are associated. It is this process that allows for generalization or the generalization of discriminations to occur through the process of imagination and is in fact the very stuff of imagination. So, for example, the alien can now imagine a motor vehicle with three wheels, or any number of wheels, without first seeing one. The alien can expect that a three-wheeled vehicle may exist or would be possible to build.

These three different processes of learning are complementary and can feed each other in constant loops. This fact, along with those of first focus above, goes a long way in describing what thinking and learning are. However, there is another property of learning worth noting, before turning to motivation to complete our description of anger responses.

This property is called blocking. This is when a previously learned association, either learned directly in the sensory environment or indirectly through transitivity, literally “blocks” the learning of other associations. Blocking occurs due to the practical limitations of our brain and sensory systems. We can only detect and process so much information at one time, and so we will only expend our limited resources in proportion to what we deem important. In other words, the environment often presents us with more information than we can process at any one time and we implicitly and or explicitly make choices about what to use our limited sensory and thought capacity to focus on. Hence, there is information in the environment that we may process late, relative to our welfare, or perhaps not at all. To illustrate, during his first minutes on earth, our alien may have noticed that there are at least two types of motor vehicles, one with four wheels and another with two. So, spending some time making and thinking about these observations, the alien suddenly notices that his delicate, relatively light-deprived skin is getting red. The alien has now learned a new lesson, though all too late, as his sensory focus and attention was on the cars and motorcycles going by. That is, that the earth’s sunlight is too intense for his delicate skin and he must now seek shelter or cover.

In extreme cases, blocking can not only delay learning, but prevent it entirely, permanently. For instance, if one develops a learned habit of focusing on only certain elements of a situation or even abstract concepts, one can easily miss differences either present from the beginning or that arise later. This can even occur with imagination, though imagination also offers another way to check against blocking. Can you imagine how this can occur?

To mention another example, in the experimental case, rats that are trained to press a lever to receive a food pellet after seeing a red light will later fail to learn to press in response to a yellow light of similar brightness, if the yellow light is first presented after learning to focus on the red light occurs. In this case, the yellow light is then presented alone and the rat will not press the lever for food.

It is important to refer to two previous concepts here, which are those of implicit and explicit memory. The newer and/or more complex the learning that is occurring, the more sensory and conscious (explicit) processing that is required. As associations are better learned, the behaviors they help motivate depend increasingly on implicit memory as learned behaviors become increasingly automatic, eventually occurring with little or no thought. This is what we call “habit” formation, and it occurs at a rate and in proportion to the sensory intensity, subjective importance, and distinguishability of the relevant stimuli.

That's the end of the section from my handout. There is more to mention here though regarding the complexity of the environments in which brains learn. One of the implications is an explanation for why people often seem to repeat mistakes, even many, many times.

Below is a section of a recent blog post:

I submit that the tasks brains are engaged are often much more complex than seems commonly perceived. All stimuli, or everything our senses can detect, become predictors for goal attainment, but usually not immediately. A process of generalization is needed, even across seemingly unrelated contexts such as different rooms in a house, or even different states of mind. For example, school children who test in the room they learn the material in perform better on average than those who are tested in a different room.

But, what if the predictive context is large and varied? Apply the counting rules in probability, and the complexity of even a "simple" task is revealed. For example, consider a mother who needs help from three kids raking the yard, and one to vaccum the house, simultaneously. Apply the permutation rule, and there are 24 different ways to assign the children to these tasks. That is, (4)(3)(2)(1) = 24. Of course, some permutations are more helpful than others, and an educated guess might mean mom can narrow down the relevant possibilities. Still, choosing the optimal permutation(s) can be very difficult, if not nearly impossible given practical limitations.

Of course, the number of permutations, which I sometimes call the permutation space, because I think it sounds cool, can be much, much greater(See other examples in the link above). Numbers can even easily get into the trillions and much higher still. This is especially true when permuation spaces are dynamic, such as in the stock market, or in social relationships. Perhaps this is a fundamental reason, along with the status quo bias and some other factors, investors often lose money seemingly employing the same strategies each time, or wives stay with abusive husbands, in many cases, trying many ways to stay with the abuser while trying to keep him calm. The actual, "blind" dynamic permutation space can be terribly, and indeed, incalculably vast,...

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

behavior analysis,

conditioning,

learning,

learning theory

Busted Myth: 10% of Our Brains

I often hear it said that we only use about 10% of our brains with the implication, explicit or implicit, that we might be able to find ways to use more of our brain capacity for thinking. Nothing could be further from the truth. The brain is chock-full with needed function, with no room for waste.

The brain has to construct our entire sensory experience, facilitate coordinated motor activity(allow for movement), store all of our relevant memories, calculate the costs and benefits of behavior, facilitate mood and emotional responses, provide a networked inborn language development faculty, and provide for many reflexes, among other duties.

It wouldn't make sense to have unused capacity in the brain, as the resources needed to keep neurons(brain cells) alive, along with carrying the dead weight in the head would be energetically wasteful. This is why unused brain cells naturally die in a process known as apoptosis.

This is just one of many myths about the brain.

The brain has to construct our entire sensory experience, facilitate coordinated motor activity(allow for movement), store all of our relevant memories, calculate the costs and benefits of behavior, facilitate mood and emotional responses, provide a networked inborn language development faculty, and provide for many reflexes, among other duties.

It wouldn't make sense to have unused capacity in the brain, as the resources needed to keep neurons(brain cells) alive, along with carrying the dead weight in the head would be energetically wasteful. This is why unused brain cells naturally die in a process known as apoptosis.

This is just one of many myths about the brain.

Energetic Behavior

The economics of behavior ultimately boil down to the efficient use of energy, as energy is obviously required for all behavior. In this sense, one can approach behavior as one does physics, at least in terms of mood and motivation.

Some of the implications are interesting. For example, a principle that applies in microeconomics is also applicable here. It is the requirement that marginal benefit equal marginal cost. To summarize for the present purpose, the energy expended on a given behavior will equal the subjective benefit, as either considered in units of energy or mood, with the latter being the ultimate currency into which all needed resources are converted.

I see mood as simply the sum of all options for net beneft(benefit - cost), discounted for time. So, not only will the energy expended in behaviors associated with each option reflect net motivation, which is obvious, but over a range of behaviors, can also reveal average mood, as previously more precisely defined.. This is when compared to some baseline measurements, which means to compare newer observations to older ones. So, the rate of change of average energy expenditure with respect to average net benefits will correspond to a range of the curve for mood, or a range on the derivative of the mood curve, to be more specific. This gives the average mood level.

The measurement of oxygen consumption, just one among other approaches, can reveal energy consumption. The measurement can be made with a respirometer, for example.

I will post about other approaches to measuring mood a various later times.

Some of the implications are interesting. For example, a principle that applies in microeconomics is also applicable here. It is the requirement that marginal benefit equal marginal cost. To summarize for the present purpose, the energy expended on a given behavior will equal the subjective benefit, as either considered in units of energy or mood, with the latter being the ultimate currency into which all needed resources are converted.

I see mood as simply the sum of all options for net beneft(benefit - cost), discounted for time. So, not only will the energy expended in behaviors associated with each option reflect net motivation, which is obvious, but over a range of behaviors, can also reveal average mood, as previously more precisely defined.. This is when compared to some baseline measurements, which means to compare newer observations to older ones. So, the rate of change of average energy expenditure with respect to average net benefits will correspond to a range of the curve for mood, or a range on the derivative of the mood curve, to be more specific. This gives the average mood level.

The measurement of oxygen consumption, just one among other approaches, can reveal energy consumption. The measurement can be made with a respirometer, for example.

I will post about other approaches to measuring mood a various later times.

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

calorimetrics,

energy,

marginal analysis,

marginal benefit.,

marginal cost,

marginal utility,

mood,

motivation,

respiration,

utility

Monday, March 1, 2010

The Unmeasured Self

I was watching a discussion this morning on youtube titled The Role of Psychotherapy in the Age of Neuroreceptors and Genes, and I have some thoughts. First though, I'd like to offer a context.

Imagine you went to your family doctor complaining of adominal pain. Your doctor refers you to an oncologist. The oncologist has just diagnosed you with a form of cancer that has an 18% fatality rate. It can also lead to increased risks for a host of other health problems short of death, such as cardiovascular diseases, reduced immune responding, and a general lethargy that could affect both your professional and personal lives.

He based his diagnosis on a family history and some rather personal questions about your lifestyle and habits, including a few questions about your medical history. He started explaining the treatment process, when you interrupt him with a question. You ask him if he will utilize more precise diagnostics, like various scanning technologies such as MRIs. He tells you that they are unnecessary and that he is sure enough about your diagnosis to to begin treatment.

Treatment will involve a painless, weekly procedure that the doctor says is often effective, though different patients are more responsive to certain doctors than others. After asking him how you'll know your getting better, he tells you that he'll chiefly base your treatment progress assessment on how you say you're feeling and whether you think it's working.

Would you feel comfortable with this diagnostic and treatment approach? Yet, this is exactly what psychotherapists offer their patients with major depressive disorder, which is fatal in about 18% of cases and can greatly contribute to the other maladies mentioned above, among many others. There is often not even a paper and pencil assessment offered during diagnosis, and there is usually no attempt at objective within-patient measurements of progress during treatment.

I'm not bashing psychotherapists here and I do acknowledge that widely known research demonstrates some effectiveness for psychotherapy in the aggregate. But still, how is the above situation acceptable? Is there an alternative?

I think there is. Other than advanced brain scans, which are currently expensive, but offer much hope in the future, a behavioral economic approach can be helpful. Since depression involves low moods, the implications of which have been described in previous posts, the resultant shift to lower risk aversion could certainly provide a definitive, quantifiable measure of progress.

This can be done in a number of ways, but to begin, you can measure the loss tolerance of patients seeking reward, such as in contests with monetary prizes. There can be opportunites to both win or lose money, with the patient keeping any earnings. This is an approach very widely used in psychological and microeconomic experiments. To note, of course changes in net personal income and assets will have to be controlled for, with the gains and losses in constant proportion.

To complement this approach, the rates of substitution between different options can be measured, to determine consistency with the more direct measure of risk attitudes, as can the ability to delay gratification and accept sooner losses.

There are also various ways to measure relative and absolute mood levels by recording behavioral investment, revealed as energy expenditure to obtain a given amount of reinforcement(pleasure). For example, energy expenditure can be measured with respirometers, heart rate monitors, etc. More energy will be expended- per-unit-gained as mood increases. This is similar to the determination in economics that marginal utility must meet marginal costs.

I personally favor the last approach, as it is more direct and requires controlling fewer variables, but I'm not sure if non-physicians are allowed to use such diagnostic techniques. The former approaches involving money are awkward, given the treatment context.

There are still other approaches, such as measuring stress hormones in saliva or examining asymmetrical EEG data, but these are also expensive, though certainly cheaper than MRIs and other brain scans.

Of course, with all of these approaches, stable baselines must be established to measure progress against.

So, there are conceivable ways for psychotherapists to demonstrate the effectiveness of their treatments in each individual and I hope more research will go into such approaches. The question is, will the therapists want to use them?

Imagine you went to your family doctor complaining of adominal pain. Your doctor refers you to an oncologist. The oncologist has just diagnosed you with a form of cancer that has an 18% fatality rate. It can also lead to increased risks for a host of other health problems short of death, such as cardiovascular diseases, reduced immune responding, and a general lethargy that could affect both your professional and personal lives.

He based his diagnosis on a family history and some rather personal questions about your lifestyle and habits, including a few questions about your medical history. He started explaining the treatment process, when you interrupt him with a question. You ask him if he will utilize more precise diagnostics, like various scanning technologies such as MRIs. He tells you that they are unnecessary and that he is sure enough about your diagnosis to to begin treatment.

Treatment will involve a painless, weekly procedure that the doctor says is often effective, though different patients are more responsive to certain doctors than others. After asking him how you'll know your getting better, he tells you that he'll chiefly base your treatment progress assessment on how you say you're feeling and whether you think it's working.

Would you feel comfortable with this diagnostic and treatment approach? Yet, this is exactly what psychotherapists offer their patients with major depressive disorder, which is fatal in about 18% of cases and can greatly contribute to the other maladies mentioned above, among many others. There is often not even a paper and pencil assessment offered during diagnosis, and there is usually no attempt at objective within-patient measurements of progress during treatment.

I'm not bashing psychotherapists here and I do acknowledge that widely known research demonstrates some effectiveness for psychotherapy in the aggregate. But still, how is the above situation acceptable? Is there an alternative?

I think there is. Other than advanced brain scans, which are currently expensive, but offer much hope in the future, a behavioral economic approach can be helpful. Since depression involves low moods, the implications of which have been described in previous posts, the resultant shift to lower risk aversion could certainly provide a definitive, quantifiable measure of progress.

This can be done in a number of ways, but to begin, you can measure the loss tolerance of patients seeking reward, such as in contests with monetary prizes. There can be opportunites to both win or lose money, with the patient keeping any earnings. This is an approach very widely used in psychological and microeconomic experiments. To note, of course changes in net personal income and assets will have to be controlled for, with the gains and losses in constant proportion.

To complement this approach, the rates of substitution between different options can be measured, to determine consistency with the more direct measure of risk attitudes, as can the ability to delay gratification and accept sooner losses.

There are also various ways to measure relative and absolute mood levels by recording behavioral investment, revealed as energy expenditure to obtain a given amount of reinforcement(pleasure). For example, energy expenditure can be measured with respirometers, heart rate monitors, etc. More energy will be expended- per-unit-gained as mood increases. This is similar to the determination in economics that marginal utility must meet marginal costs.

I personally favor the last approach, as it is more direct and requires controlling fewer variables, but I'm not sure if non-physicians are allowed to use such diagnostic techniques. The former approaches involving money are awkward, given the treatment context.

There are still other approaches, such as measuring stress hormones in saliva or examining asymmetrical EEG data, but these are also expensive, though certainly cheaper than MRIs and other brain scans.

Of course, with all of these approaches, stable baselines must be established to measure progress against.

So, there are conceivable ways for psychotherapists to demonstrate the effectiveness of their treatments in each individual and I hope more research will go into such approaches. The question is, will the therapists want to use them?

Labels: anger, classes, psychology, evolution

depression,

emotions,

major depression,

major depressive disorder,

mood,

psychologists,

psychotherapists,

psychotherapy,

treatment

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)